Vannevar Bush

I found Vannevar Bush intriguing

because of his conception of Hypertext before there was even a thought of the

WIMP interface that would make it possible. He conceived a physical machine

called the Memex that would allow a

user to access multiple documents in a non-linear, relational manner. I was

really curious how he imagined this would be implemented physically without the

virtual environment of a WIMP-based computer.

I found Vannevar Bush intriguing

because of his conception of Hypertext before there was even a thought of the

WIMP interface that would make it possible. He conceived a physical machine

called the Memex that would allow a

user to access multiple documents in a non-linear, relational manner. I was

really curious how he imagined this would be implemented physically without the

virtual environment of a WIMP-based computer.

The Memex

was never realized, but it was merely one idea amongst an otherwise very

accomplished career. His biggest footprint on history was his contribution to

the overall role of science in our society. His work changed how scientific

research is conducted in America.

His earliest

contributions were to the World War I efforts, as part of the National Research

Council (NRC), where he offered up an invention to detect submarines. In the

1930’s he worked on analog computers,

and developed a differential analyzer,

which used gears and other mechanical parts to solve differential math

equations. At this time, his focus also turned to developing rapid selector machines to help manage

and interact with information in microfilm form.

When he

became president of the Carnegie Institution, this put him in a position to

influence the direction of research in the U.S. and advise government on

scientific matters. But it was World War II that prompted him to meet with

President Roosevelt and propose a new organization for military research – the National

Defense Research Committee (NDRC). Prior to the NDRC, there was not much

coordination between the government, military, business and scientific

communities. Bush was named chairman, and later the director of the

organization’s later incarnation, the Office of Scientific Research (OSRD).

Among some

of the developments of the NDRC/OSRD were improvements in radar, the proximity

fuse, anti-submarine tactics. At his direction, the NDRC/OSRD created a

newfound respect for science and the need for government support for science.

Colliers magazine even claimed he was the “man who may win or lose the war.”

Bush

returned to his prior work regarding rapid selectors to conjure up the Memex in

an article for the Atlantic  Monthly magazine titled “As We May Think.”

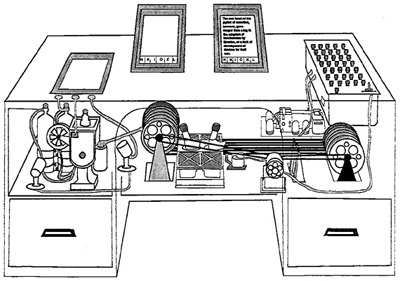

It would be a desk-sized machine with microfilm viewing screens, along with a

keyboard, buttons and levers. The collection of microfilm would be stored

internally within the desk. But the novelty of it wasn’t simply being able to

automate the retrieval of multiple microfilm documents, but rather the ability

to form and store logical correlations between documents.

Monthly magazine titled “As We May Think.”

It would be a desk-sized machine with microfilm viewing screens, along with a

keyboard, buttons and levers. The collection of microfilm would be stored

internally within the desk. But the novelty of it wasn’t simply being able to

automate the retrieval of multiple microfilm documents, but rather the ability

to form and store logical correlations between documents.

Bush realized the amount of written information being generated by society was so copious, that some sensical way to aggregate it had to be devised. But he also foresaw multimedia: “Today we make the record conventionally by writing and photography, followed by printing; but we also record on film, on wax disks, and on magnetic wires. Even if utterly new recording procedures do not appear, these present ones are certainly in the process of modification and extension.”

But regardless of information medium, at the heart of his idea was “selection by association, rather than by indexing.” He felt that this was more in line with how the human brain really works, and information retrieval devices should work similarly.

But how would these associations be made, I wondered? He describes “a provision whereby any item may be caused at will to select immediately and automatically another… The process of tying two items together…” Bush envisioned each document being assigned a code, displayed below the document on the display. The codes could merely be used to retrieve individual document in a traditional linear fashion. But the Memex would have allowed for two documents to be viewed side-by-side, and then for the user to ‘join’ their two codes by pressing a button. This would create an inherent link between them, so that when one was retrieved, the other would be noted in context and made available for non-linear reference.

Vannevar never saw his device realized. He died in 1974, well before the concept he described (now known as Hypertext) would be realized by computers, the Internet and the World Wide Web.

Sources

“Internet

Pioneers: Vannevar Bush” http://www.ibiblio.org/pioneers/bush.html

“As We May

Think”, Vannevar Bush, The Atlantic Monthly, July 1, 1945 http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1945/07/as-we-may-think/303881/4/